I’m partial to efforts committed to turning down the temperature of our politics. I’m proud to serve on the boards of two organizations—the American Values Coalition, and Neighborly Faith—doing that in different ways. And I’m always interested in hearing how people are taking proactive measures to work within and alongside faith communities for the purpose of combating political extremism and toxic polarization.

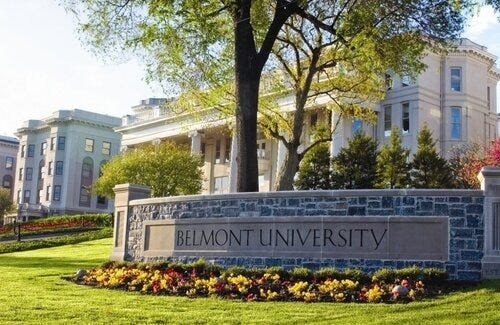

Which is why I was encouraged to hear that a pair of researchers—one at Belmont University, the other at the University of Washington—recently received a major grant to “research the likelihood of religious engagement to reduce political polarization in the U.S.”

From Belmont’s press release:

The three-year study, led by Dr. Adam Smiley of Belmont and Dr. Cheryl Kaiser of the University of Washington, will investigate how religious practices and beliefs might foster intellectual humility and compassion, potentially decreasing affective polarization between Democrats and Republicans.

”This research is crucial for identifying approaches to increase tolerance and civility in our politically divided nation,” said Smiley. “Ultimately, our goal is to understand if deeper engagement with one's faith can lead to more tolerant attitudes across political divides. We hope to promote social cohesion and human flourishing through our findings.”

It’s an ambitious project, combining large-scale surveys with in-depth focus groups in Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities. One assumption of the project is rooted in the role religion plays in developing social capital, which has the potential to temper people’s most extreme proclivities in their political engagement. As institutional religion continues a slow yet steady decline in the United States, cultivating social capital becomes even more important.

I’m looking forward to seeing what these researchers find.

Recommended Reading

More Christian Colleges Will Close. Can They Finish Well? (Nadya Williams, Christianity Today)

US birthrates dropped to an all-time low during the Great Recession and never bounced back. Next year, in 2025, we’ll be 18 years past that initial plunge, and our national birthrate remains below replacement level.

All things being equal, this means that every year for the foreseeable future, the entering freshman class in colleges nationwide will decline. Harvard will probably be just fine. Tiny Christian colleges without a national reputation, not so much. Even Wheaton College, the “evangelical Harvard,” had to make adjustments for this reality in late 2022.

Going forward, nearly all Christian colleges will have to plan to shrink, merge, or close. These difficult choices will be unavoidable and necessary. But, to get back to the question I posed at the outset, how college leadership approaches these decisions matters, and how Christian college leadership does it should be recognizably shaped by Christian ethics.

A Change of Age (John Seel)

We are as a Western Christian church at an historic inflection point. We are at a point of decision. To meet our moment, we will need the courage to face these realities, the humility to seek God's leading, and the discernment to balance innovation with historic orthodoxy.

We must embrace the tension this causes, the cognitive dissonance to our faith, and move forward with enthusiasm for we have the opportunity of living in one of the most exciting moments in church history in the past 500 years.

We are being called to the breaches to make our stand. The circumstance we face are new. Our God and his kingdom resources are not.

Democracy Needs the Loser (Barbara Walter, The New Yorker) — pairs well with my 2021 Christianity Today article, “We Need to Be Better Losers”

When people think of elections, they usually focus on who might win and the policies that the winner is likely to enact once in office. But equally important in a democracy is how the loser reacts. If he or she does not accept the vote, then portions of a country can become ungovernable…. Democracies survive only if losers accept the results.

History tells us that the groups that initiate violence tend to be those which had once been politically dominant but are in decline. If Trump loses again, the more extreme members of the MAGA base will have even more evidence that the system no longer works for them, and that their chance of winning in the future is going to plummet. They will lose hope in our federal government, and in our democracy.

The World Says Accelerate. The Church Says Abide (Aryana Petrosky, Christianity Today)

In The Congregation in a Secular Age, Andrew Root makes the case that our modern experience of time is a type of famine—an unsatiated desire for not just more hours in the day, but for a fuller and more meaningful experience of each passing moment. Silicon Valley asks us to innovate, accelerate, and maximize, making it possible to endlessly multitask, to do more and more quickly. Ironically, devices that purport to save us time make us feel like we never have enough. We can’t slow down long enough to hear ourselves think, let alone hear the whispers of the Holy Spirit.

This freneticism makes it especially difficult for the church to guide congregations into sacred time. Instead, “time is emptied for the sake of speed”; the church’s purpose becomes change, compulsive growth, rather than “transformation in the Spirit.” We need the church to go against the cultural tide of acceleration and to be a place where we learn to inhabit the holy, mysterious, and eternal.