Getting to Know You: James Wood

Talking with the professor and author about mission as cultural engagement, kindness versus winsomeness, and national conservatism

Every once and a while I’ll be interviewing interesting people at the intersection of faith, politics, and public life. These interviews will take place via email, edited for clarity and length, and then shared with you.

Next up in this series is James Wood. James is an assistant professor of ministry at Redeemer University (Ontario, Canada). He earned his doctoral degree in theology at Wycliffe College, where he wrote on Henri de Lubac. Previously, he worked as an associate editor at First Things, as a PCA pastor in Austin, TX, and as a campus evangelist and team leader with Cru Ministries at the University of Texas at Austin.

In our conversation James talks about his viral essay on Tim Keller, how he differentiates between kindness and winsomeness in Christian political engagement, what he would say to a young person thinking about how to faithfully engage with the culture around him or her, and more. As you can see from his responses below, he was very generous with his time.

With that, here’s James Wood.

Daniel Bennett: You’ve had an interesting journey to your current position at Redeemer University. How did your work in college and pastoral ministry lead you to think and write about the future of Christian cultural engagement?

James Wood: Yes, it has been an interesting journey to this teaching position. Upon completing undergraduate studies at the University of Texas, I began a career as a minister — first as a campus missionary and ministry team leader, then as a pastor, all in Austin, TX.

My interest in the topic of cultural engagement came early on in my Christian life. I became a Christian in college while I was in a secular fraternity. Immediately my heart stirred for mission, wanting to reach my fraternity brothers with the gospel. During that time I started reading apologetic materials, but also I was guided by the writings of Tim Keller who helped me understand the broader culture and the predominant worldviews shaping my friends. Thinking about culture was always driven by a passion for mission.

At the same time, I have always been interested in the intersections between the theological and the political. I was drawn to the “postliberal” discourse around 2005, as I began to reflect on how our political order shapes our theological imagination. Then I dove into the writings of Newbigin, Hauerwas, NT Wright, and Leithart and began to ponder the inherently “political” nature of the faith. After pastoring through the 2016 election, I realized I had more questions I wanted to explore in depth, and therefore pursued doctoral studies.

DB: Your First Things article on Tim Keller generated a lot of attention. Did that surprise you? Was there something you thought critics of the piece didn’t quite get about why you wrote it?

JW: I really didn’t start writing popular-level essays until a couple years ago. In the midst of all the chaos of the past few years, I found myself in many back-channel, private conversations about the tense issues of the day. It seemed that some of my reflections were used by God to help others. Over time, I felt a sense of calling to step into the public arena and share some of these thoughts in hopes of serving others.

I never thought I would write about Keller. That essay originated over a lunch chat with Rusty Reno while I was working at First Things. I simply shared that I had noticed that a lot of former fanboys of Keller, like myself, had shifted away a bit from looking to him for guidance as it pertains to cultural engagement in our contemporary context. Once I told him my dog’s name, Rusty told me I had to write an essay. I hesitated at first, but became convinced that it might be helpful to explain some of the reasons why many had pivoted in a similar way, but also to do so as someone who still greatly admires Keller.

I figured this would ruffle the feathers of some, but I had no idea it would function as a bomb in the playground of the winsome warriors.

No, I had no idea it would receive the response it did. Seriously. I had written more provocative pieces prior to that, and they were mostly ignored. I figured this would ruffle the feathers of some, but I had no idea it would function as a bomb in the playground of the winsome warriors. It was by no means, however, an attempt to “farewell” Tim Keller—it is ridiculous to even imagine I could have such an influence, and it grieves me that some think that was my desire.

DB: One of the things your critics have suggested is that you want Christians to abandon “kindness” in our political engagement. I can’t imagine that’s the case. Could you distinguish between winsomeness and kindness in Christian political engagement, and how kindness might look apart from winsomeness in a negative world?

JW: Yes, this charge has popped up often, which I find strange, at least for two reasons. First, I have repeatedly explained that this is not what I am arguing for. And second, I don’t believe I have been unkind in my public statements, and I intentionally try to avoid the impulse to “own the libs.” I also regularly speak up about refusing to engage in bulverisms — making assumptions about your interlocutor’s motives in such a way as to discredit their arguments by virtue of their supposed immoral motivations.

Two quick comments on winsomeness and kindness. Kindness is a non-negotiable command of Christ and fruit of the Spirit. No context repeals the call to kindness. However, the biblical moral vision does not reduce to kindness; or, rather, whatever kindness means must also make room for other elements of the biblical vision that might appear as “unkind” to some. Many fellow travellers in this conversation go immediately to the hard words of Elijah against the prophets of Baal or Jesus flipping tables, but detractors think these are extreme exceptions.

But what about the consistent hard words in Scripture toward false teachers? Or when the book of Acts tells us that Paul, being “filled with the Spirit,” called the prophet/magician Elymas, who was opposing Paul's teaching and the ways of the Lord, a “son of the devil,” an “enemy of all righteousness, full of all deceit and villainy” (Acts 13:8-10)? Or Jesus’ harsh words to the scribes and Pharisees in Matthew 23? Are these “unkind?” I would say no, since, as CS Lewis once remarked, “The harshness of God is kinder than the softness of men.” Sometimes love might appear unkind, but truthful love requires, at times, hard words.

The biblical moral vision does not reduce to kindness; or, rather, whatever kindness means must also make room for other elements of the biblical vision that might appear as “unkind” to some.

My second comment here is that this will be increasingly true in “negative world.” As our broader culture increasingly repudiates concern for biblical morality and any recognition of natural law, Christians, in their efforts to honor God and love neighbor through politics, will face heated pushback that their views are harmful and unloving, or “unkind.” My concern is that they will buckle under these pressures if they are overly oriented to how they are perceived. If, even when they try to be as winsome as possible, they are regularly denounced as unkind in their pursuits of influencing the public order with their Christian convictions, I worry that many will begin to think that these Christian convictions are themselves wrong. I worry about this accommodationist temptation that will become more and more acute as we continue to enter later stages toward a fully post-Christian society. I don’t want Christians to be jerks, but I do want them to prepare to be called jerks (and the like) when they uphold biblical teachings. I want them to stand firm.

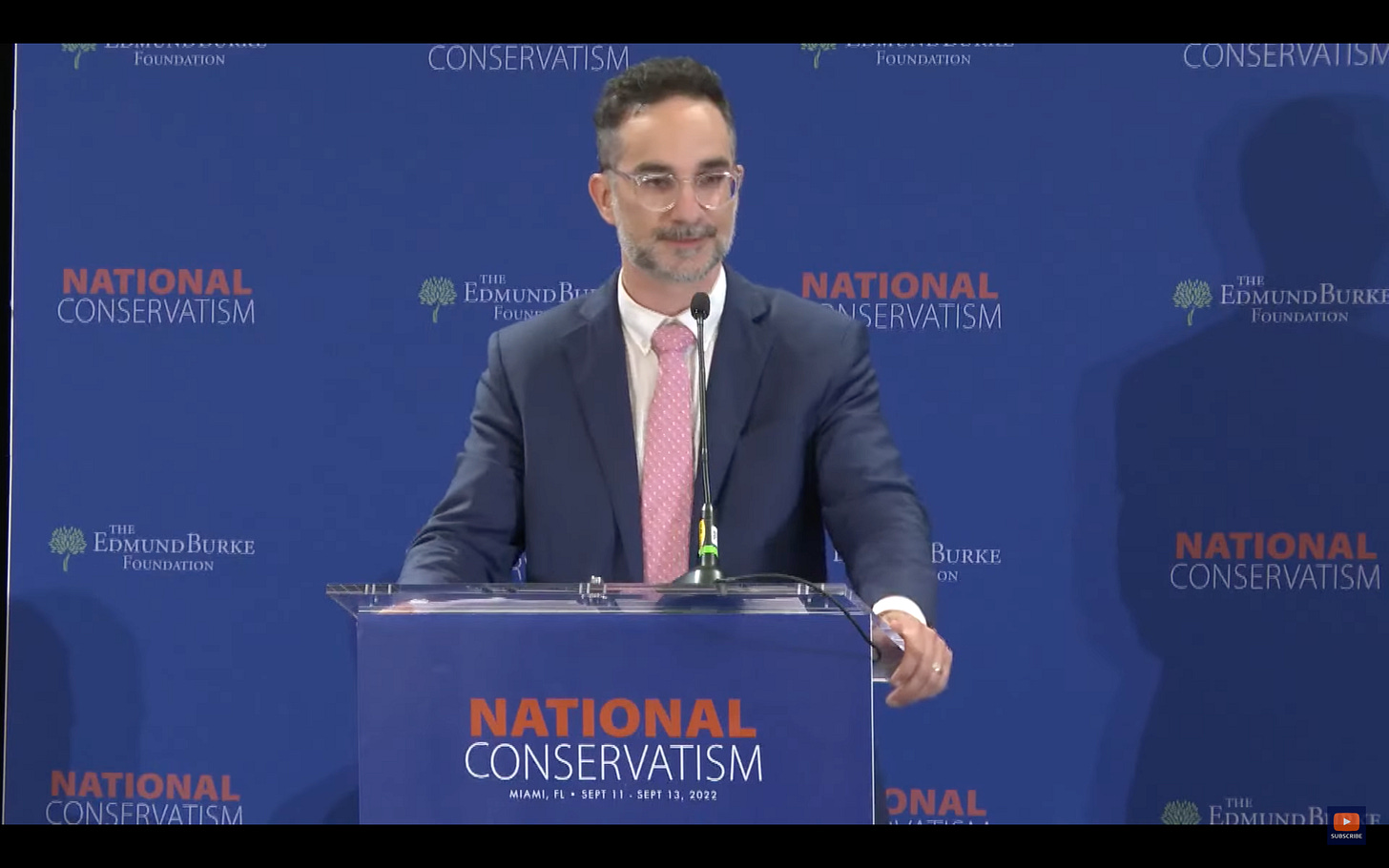

DB: Earlier this year you spoke at the NatCon conference, on the limits of winsome politics. What’s one thing you especially admire about national conservatism? What’s something NatCon does or believes you happen to disagree with?

JW: I am new to the NatCon world. But I appreciate many things about it. [Yoram Hazony] is a devout Jew who wants people to honor God first and foremost. He is anti-revolutionary, including counter-revolutions. He continues to emphasize that conservative renewal must begin in the personal lives of individuals and families. However, Yoram and most involved in the NatCon orbit also recognize the folly of the simplistic slogan, “Politics is downstream from culture.” No, there is a complex, reciprocal relation between politics and culture. Classical political philosophy and Christian political theology recognize that law is a teacher, and cultural conditions conduce to right behavior, affections, and faith. Thus, there is a renewed interest in Magisterial Protestant political theology in the NatCon world. I think this is a salutary development that could benefit Christian discourse on the political more broadly in America.

I don't know that I strongly disagree with “NatCon” on much, since NatCon is a complex coalition. I guess if you were asking about the recent Statement of Principles, an area of difference between my passions and the particular principles laid out there is that I want to place explicit emphasis on the church as the central site of a Christian’s social imagination. I don’t fault the statement for this since it had a different objective in mind (to outline shared commitments of a broad, interfaith coalition), but that is a difference. The statement itself can also be interpreted as downplaying universal truths and international goods, especially with the strong statement about “independent nations” — I would prefer to say something like “interdependent” and cooperative nations, but this is not a strong disagreement, rather a slight difference in emphasis. But I do worry about how some could run with the statement in a direction that instrumentalizes the Christian faith for national ends.

I am a nationalist of some shape, but my transnational, trans-epochal ecclesial identity relativizes and transforms this national loyalty in certain respects. And I think there can be a temptation to read the statement about how the Bible is beneficial to public order and serves as a source of Western civilization as translating Christianity into a civil religion that is ultimately subservient to temporal politics. I don’t think that is the intention behind the statement, but it is a concern I have about possible readings.

DB: As someone who works with young adults regularly, what is some advice you’d give them as they think about how faithfully engage with the culture?

JW: I have really just begun to work with young adults again after a doctoral hiatus. So these are just some loosely formed, grab-bag thoughts at present.

I will start by simply restating neo-Calvinist basics: we must engage culture with recognition of both common grace and antithesis, both a “yes” and a “no” to every culture, institution, and artifact — celebrating how these reflect creational goodness but also critiquing and correcting fallen misdirection and idolatry. That is neo-Calvinism 101, and I agree.

Though I have become known for my critiques of winsome politics, my main passion … is to focus our social life in the church. If you do that, this will help you put temporal politics in their proper place.

Furthermore, we have to act Christianly in every sphere. No sphere is beyond the borders of Christ’s rule. However, different spheres have different emphases. Thus, as I have argued, our political engagement should not be approached through the lens of evangelism, but rather according to the prudential pursuit of justice.

Some other thoughts related to our moment: reject bulverisms and other forms of making assumptions about motives. Instead, engage explicit arguments and exhibited tendencies. Something I have been wrestling with recently is the tension between steel-manning your opponent’s position but also recognizing the manipulative motte and bailey tactic that is regularly deployed in our current discourse.

Lastly, though I have become known for my critiques of winsome politics, my main passion (reflected in my dissertation, master’s thesis, and many other writings) is to focus our social life in the church. If you do that, this will help you put temporal politics in their proper place.

DB: What are two or three books you think all people interested in faith and public life should read to better make sense of our world today?

JW: Oh gosh, the books question. So many. If your readers want to get serious, then these: A Secular Age, by Charles Taylor; Public Religions in the Modern World, by José Casanova; The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, by Carl Trueman; City of Man, by Pierre Manent; Separation of Church and State, by Philip Hamburger; and Desire of the Nations, by Oliver O'Donovan. For a more playful, accessible work, Against Christianity, by my good friend and podcast co-host Peter Leithart.