Goodbye to the Johnson Amendment

Plus, some reading recommendations and a salute to Cal Raleigh

Last week the Internal Revenue Service and Department of Justice wrote in a legal filing that it would no longer enforce 26 U.S. Code § 501(c)(3), also known as the Johnson Amendment. Moreover, the Trump administration indicated it would encourage courts to consider the statute’s constitutionality moving forward.

The Johnson Amendment specifies which organizations are eligible for exemptions from federal income taxes. Exemptions are available to organizations—including religious groups— that “do not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.” In layman’s terms, the Johnson Amendment states a church can lose its tax exempt status if its pastor endorses a candidate from the pulpit.

In practice, the Johnson Amendment has rarely been enforced. The Christian legal group Alliance Defending Freedom organized Pulpit Freedom Sunday for years, encouraging churches and their pastors to deliberately violate the Johnson Amendment—and to send evidence of their violations to the IRS—in an effort to provoke a lawsuit to legally challenge the provision. But the government has historically shown little interest in the onerous task of monitoring and picking fights with religious nonprofits, including churches.

The Trump administration’s latest statement effectively puts the final nail in the coffin of the Johnson Amendment (at least for now). This means, according to the headline from Christianity Today’s reporting, that “churches can endorse political candidates.”

There are two sides to this story. One side is constitutional—namely, whether the government violates the First Amendment when it effectively tells organizations what they can and cannot say under threat of financial penalty. The DOJ’s filing likens a pastor’s sermon to “a family discussion,” and that the content of a sermon (including potential political content) amounts to “bona fide communications internal to a house of worship.”

If the content of sermons are protected by the First Amendment (and they surely are), then all the content should be protected, including endorsing a candidate for political office.

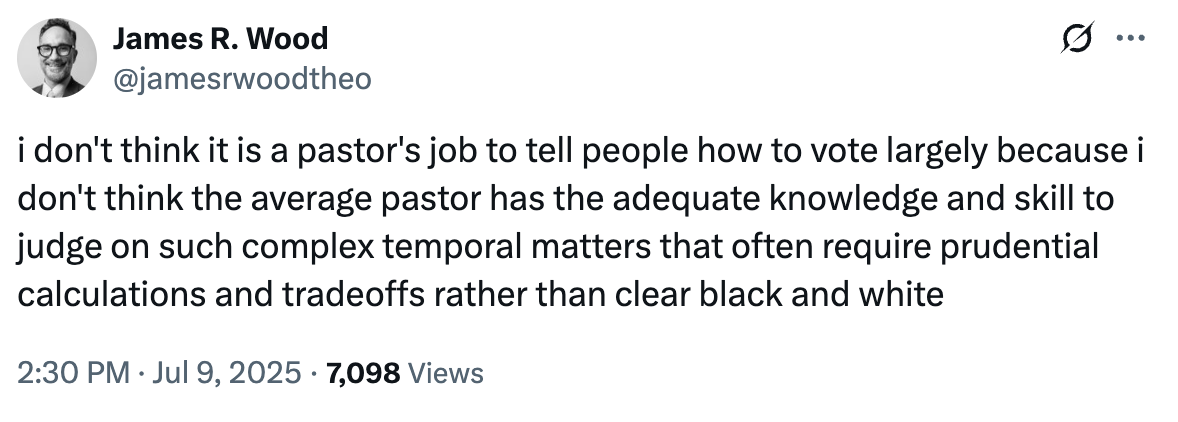

The other side of this story is prudential — namely, whether a pastor should make political endorsements in his official capacity. Here’s theology professor James Wood on this question:

This is basically where I land. On the one hand, it’s naive to think the Bible offers no wisdom or judgment on the political affairs of Christians. After all, as Paul writes in his second letter to Timothy, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.”

Our political decision making is not exempt from scripture, in the same way that our actions and behaviors concerning money, work, family, and myriad other elements of our daily lives are implicated in biblical teaching. If pastors can speak to those things (and they should), why not politics?

On the other hand, it would be easy for pastors to begin to prioritize narrow politics at the expense of exegetical teaching — even with good motives, the temptation of partisan politics in today’s pernicious and often toxic environment is real. Coupled with the acknowledgment that political decisions are going to be imperfect (after all, individual candidates are, like us, fallen and sinful people), there is a danger in elevating prudential decisions—such as voting in an election—to the same level as clear and grounded biblical teaching.

My simple take: Pastors should continue to speak truth wherever it leads, but they should not do so selectively in order to advance a narrow, partisan political agenda.

As fate would have it, I’m currently in the early stages of a new research project on how pastors understand their responsibilities to politics in their congregations. I plan to interview pastors (primarily from evangelical congregations) around Northwest Arkansas in order to understand what drives their decisions to address (or not) politics from the pulpit.

It’s hard to imagine a more relevant development for this project than the demise of the Johnson Amendment.

Before we get to some recommended reading, I’d be remiss if I didn’t pay my respects to Cal Raleigh, the Seattle Mariners’ catcher who is having the best power hitting season in franchise history. The evidence:

Raleigh entered the All-Star break with 38 home runs in 94 games, already four more than he’s ever hit in a whole season

Raleigh is on pace for 64 home runs, which would break Aaron Judge’s American League record for the most ever (62). And even if Raleigh’s numbers dip a bit over season’s final 68 games…

Raleigh is well on his way to break Ken Griffey, Jr.s’ team record for home runs in a season (56), as well as the single-season record for catchers (48)

Incredibly, Raleigh is doing this as a switch-hitter — he’s hit more home runs as a left-handed batter, but he’s still hit more than a dozen from the right side of the plate

Oh, and he also won Monday night’s Home Run Derby, becoming the second Seattle player ever to win the event (again, shoutout to Ken Griffey, Jr., who won three times).

So kudos to you, Cal Raleigh. May you continue to hit baseballs into orbit, and maybe even write your name in baseball’s record books.

Recommending Reading

A Victory for Religious Liberty (Law and Liberty)

Joseph Griffith describes the Supreme Court’s decision in Mahmoud v. Taylor (which I wrote about here) as a potential strike against the “official” precedent on religious freedom, Employment Division v. Smith:

Mahmoud’s reliance on Yoder, instead of Employment Division v. Smith (1990) and its progeny, portends a welcome and potentially significant shift in the Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence, a move Justice Alito has been urging the Court to make for years.

In Smith, the Court held that the First Amendment does not protect otherwise illegal activity from neutral, generally applicable laws. In effect, it meant that the government may incidentally burden, but not target, a religious belief or practice.

He continues:

While Mahmoud does not directly overturn Smith, Justice Alito’s majority opinion may be signaling his intention to let it atrophy by neglect, though it is too early to tell with certainty. To me, his reason for not following Smith remains cryptic: “In most circumstances,” the Court uses the Smith test, but “the character of the burden requires us to proceed differently,” he writes. What about “the character of the burden” in this case justifies this departure? For those concerned about the right to freely exercise religion or the role of religion in public life more broadly, it’s time to celebrate the Court’s decision in Mahmoud—and to carefully watch for Alito’s next move.

The church I led closed a year ago. I’m still not over it (Deseret News)

Ryan Burge reflects on his church’s closure, one year later. Specifically, he reflects on all the emails and advice he’s received after various media outlets covered of the closure. Some, he writes, weren’t especially helpful:

They all had an air of superiority about them — the writers were sure they understood the problems facing First Baptist Church better than I did, when I served as the pastor of that congregation for more than 17 years.

I grew up in an evangelical church, and I have to admit that the general worldview of evangelicalism is still deeply rooted in my psyche. I knew where were coming from: no one is beyond the redemption of Jesus Christ and so there’s no church that can’t be saved by a little bit of religious revival.

Many corners of the Christian world have this foundational optimism, believing that all the ills facing the American church are going to be solved when that next revival comes — and it’s certainly right around the corner. But the composers of these “I can save you” emails did not understand that I and my congregation were just completely exhausted — physically, spiritually and financially, we were on our last legs. The church closing its doors was a burden lifted off our shoulders, a weight that some of them had been carrying for decades.

Not every church needs to be saved. Sometimes, they need to die.

How the Attention Economy Is Devouring Gen Z — and the Rest of Us (The Ezra Klein Show)

Ezra Klein’s interview with Kyla Scanlon is worth a listen in its entirety, but I found their discussion of friction especially important:

EK: Give me your theory of friction.

KS: Basically the idea of friction is that there is value in things being a tiny bit difficult.

When we use digital tools, there really isn’t a lot of friction. For instance, dating apps make dating very easy. DoorDash makes things coming to your house very easy. You can have this frictionless existence.

You also have an algorithm that’s designed around you, serving up anything within your echo chamber. You never really have to think outside of what you’re already thinking unless you choose to.

Whereas in the physical world, there’s a lot of friction. If anybody has flown over the summer, it might have been a challenging experience. We don’t have enough air traffic controllers, and we don’t have enough people doing maintenance on the plane.

It’s just little things that feel like they should be simpler and running smoother. And they’re not, because they’re not part of the digital universe, which gets so much money and investment.

It’s this idea that there’s a bunch of friction in the physical world, and perhaps not enough in the digital world.

EK: Do you think those things are connected? That there’s so much friction now in the real world, in actually building and accomplishing things, that it has created this flight to the digital world? That people are overinvested in the digital world because we’ve done such a bad job managing friction in the real world?

KS: Yes. It’s just easier to be online. You don’t have to reckon with stuff. You can create this curated experience. My boyfriend talks about it all the time: You can present this perfect appearance. And people write about this, too. Your Instagram page is a collection of your best moments ever. So you can kind of have this life that isn’t your life. Whereas in the physical world, you might just be dealing with headache after headache: How do I pay this bill? How do I make rent this month? How to make sure I’m still succeeding in my job. All of those things.

EK: For you there’s a connection between friction and meaning — or frictionlessness and meaninglessness. How do you draw that?

KS: I think the idea is that when things are a little too easy, it’s tough to find meaning in it. The way I think it might be best to visualize it is from “WALL-E.” If you’re able to lay back, watch a screen in your little chair and have smoothies delivered to you — it’s tough to find meaning within that kind of WALL-E lifestyle because everything is just a bit too simple.

The good parts of life often come through the hardest struggles, and I think that is where people do find a lot of meaning. That’s what all the greats write about: the struggle and the path.

Keep pushing the rock up the hill, more or less.

Also making an appearance in their conversation: C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters. Like I said, the whole thing is worth a listen.