Uneasy Citizenship teaser: "The Polarization Problem"

The challenge of political polarization to Christian political engagement

In the weeks ahead, I’ll be sharing excerpts from my in-progress Uneasy Citizenship book manuscript. This week, it’s Chapter 3’s “The Polarization Problem.”

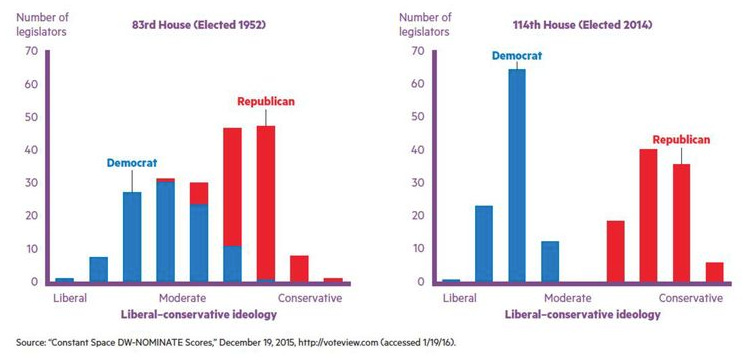

One of my favorite things to share with students in my introductory American Government and Politics class is a figure on the changing complexion of Congress. No, not in terms of the gender of its representatives, or their religion, or their race, but in terms of their ideology. In 1952, the House of Representatives was divided amongst Republicans and Democrats, just as it is today. But the ideology of House members looked quite different: on a liberal—moderate—conservative spectrum, there were liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats, so that the distribution of House members’ ideology resembled a Bell curve of sorts.

Sixty years later, in 2014, the situation had changed. That Bell curve, with a healthy and robust “middle” section comprised of both Republicans and Democrats, was gone. In its place was a figure that more closely resembled a bimodal distribution, with almost no overlap in the middle and increasingly high numbers of conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. Gone were the days of the moderate middle in terms of congressional ideology; polarization had transformed the institution and its membership, reflecting a steady trend in American society.

As a political scientist, a lot of my reading, research, and teaching involves polarization, which, in my discipline, refers to people, parties, and groups growing further apart. This is often discussed in ideological terms, classifying people as either conservative or liberal. But polarization can be found in virtually any aspect of American society, moving beyond the political and influencing what movies and television programs we watch, what sports we enjoy, and even where we eat. More and more, people seem to be looking for ways to highlight their opposition to one another while simultaneously huddling with people who think like them. This is not a recipe for a healthy culture.

Christians are as susceptible to the pitfalls of polarization as their fellow citizens. We live in a fallen world, and sanctification does not equal perfectionism. But for Christians, tasked with making disciples of all nations and peoples, polarization, while in some sense inevitable, is especially dangerous. Yes, polarization discourages the sort of cooperation and compromise necessary for our system of government. But more importantly, it encourages categorizing people simplistically as either allies or opponents, when we should instead be seeing them as made in the image of God.

In this chapter I draw on research from political science to show the pervasive and problematic role polarization plays in American politics and society. I begin in 1950, with a major report from the American Political Science Association on the then-odd state of the country’s two major political parties. I then move to a seminal study on the weaknesses in most people’s ideologies, written in 1964 but still quite relevant today. I then highlight recent research on polarization, focusing on studies showing how polarization affects people’s daily lives, before concluding with the troubling implications of polarization today, ranging from delight in the misfortunate of others to support for violence against political opponents.

Polarization of the sort described in this chapter is a significant challenge to Christians’ witness to the world. If we are learning to view others with contempt or inherent suspicion as a result of their political inclinations—whether they are fellow Christians or just fellow human beings—we are not giving them the respect they deserve as created in God’s image. And when we allow politics to fundamentally alter these relationships, it becomes an idol we must wholeheartedly reject. To combat this challenge, though, we must first understand it.