A thrill of hope, the weary world rejoices, for yonder breaks a new and glorious morn.

There is a richness in so many of our Christmas hymns and carols. “Peace on earth, and mercy mild; God and sinners reconciled.” “The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight.” “Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel shall come to thee, O Israel.”

But the above lyric from “O Holy Night” especially gets me. The idea of a waiting and weary world rejoicing in the arrival of Jesus—God incarnate, with us—ought to quite literally thrill us with hope. The dominion of sin and death began to end with the birth of Christ, ushering in a truly glorious dawn.

For those of us who grew up in the church and have heard the Christmas story for decades, it can be easy for this wondrous and miraculous story to fall on numbed and tired ears. But listen this short description of the incarnation from Sinclair Ferguson, and join me in wondering how we could ever not be overcome with excitement and hope for our future every time we reflect on the birth of our Savior.

So for now, we wait. We busy ourselves with the tasks of the day. We care for our families, work our jobs, pay our bills. But in our waiting and our toiling let us not forget to be awed, to be filled with the thrill of hope that comes with the new and glorious morn to come. Let us not forget to rejoice in our weariness. For as it was told to the shepherds in Luke 2, so it is forever told to us:

“Fear not, for behold, I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all the people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord.”

Merry Christmas.

Embracing our Uneasy Citizenship in 2025

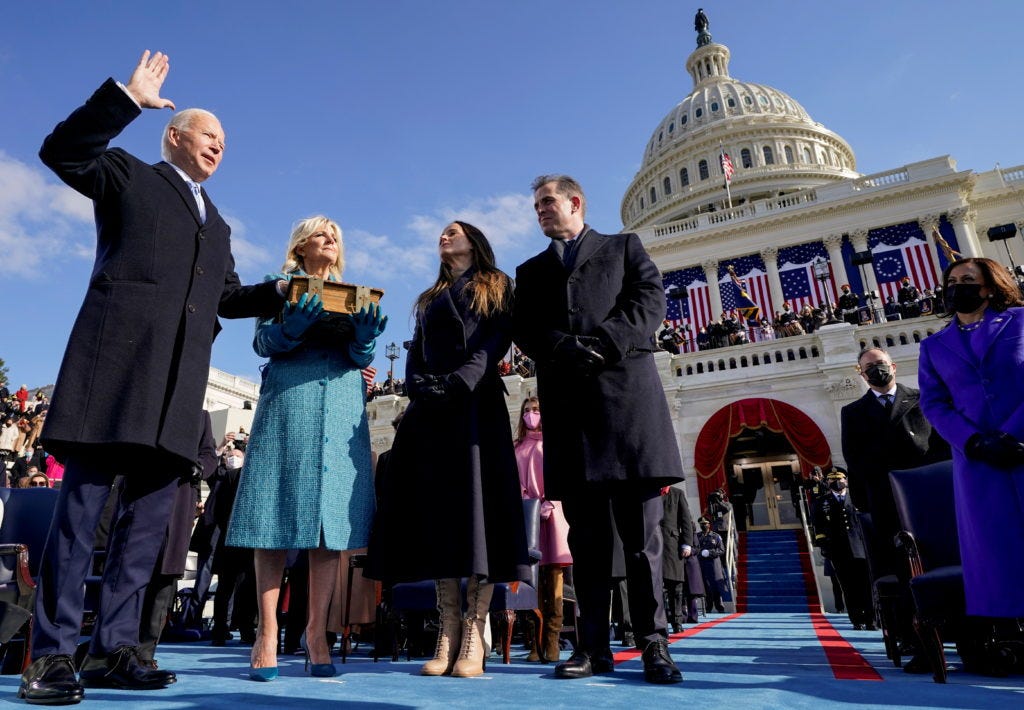

Can you believe we’re exactly a month away from Inauguration Day 2025? I’m a bit of a sucker for the pageantry and symbolism taking place every four years on January 20, especially when there’s a transition between presidential administrations. It was discouraging to see that transition suffer nearly four years ago, and I can only hope that former President (and President-elect) Trump represents a one-time departure from those established norms.

Whether you’re eagerly, anxiously, or fearfully awaiting the next four years, I’m glad to be on this journey with you. And if you haven’t read my book, Uneasy Citizenship, yet, a new year is a great time to do it! You can order a copy in a couple of ways:

Buy from Amazon, ChristianBook, or direct from the publisher

Request a signed copy from me — it might even be cheaper that way!

And don’t forget to review it wherever you can!

I’m so grateful for your support, especially this past year. Here’s to a faithful and hopeful year of politics in 2025.

Reading Recommendations

Against Christian Civilization (First Things)

Paul Kingsworth examines the recent tendency among some Christians—Protestant and Catholic—to declare it a semi-religious imperative to save our waning culture. He warns:

Is the decline of Christianity responsible for our current malaise? Is our lack of faith at the root of our loss of confidence and the ensuing inversion of our old values? The answer to this, in one sense, is obviously yes. As another historian, Tom Holland, demonstrated in his book Dominion, it was Christianity that formed the Western mind. When such a sacred order dies, there will be upheaval at every level of society, from politics right down to the level of the soul.

This, I think, is where we are. And I am hardly the only one to have noticed. In fact, almost everyone who is paying attention has by now noticed. Some of those people, in response, have come to a conclusion: Since Christianity was the basis of this “Western” culture of ours, and since this culture is now sick or even dying, the way to revive it must be to revive Christianity—not so much as a religion, but rather as a social glue, or even as a weapon. What we need, we increasingly hear from many different quarters, is a return to something called “Christian civilization”—regardless of whether the Christian faith is, in fact, true.

At a certain level, this might appear to be an attractive narrative. But I believe it is a deadly mistake.

Importantly, he concludes:

I think now that we will recover a culture worth having only if we tune our radio dials to humility, as persons and as peoples. Our work is not to “defend the West.” That’s idol worship. Our work is repentance, which means transformation. We have to be prepared to die—and thus reborn. I am speaking as someone who is, most of the time, afraid even to contemplate what this might demand of me.

But I believe there is wisdom to be found for us, in this disintegrating age, not in crusading knights or Christian nationalists, not in emperors or soldiers, but in the mystics, the ascetics, the hermits of the caves, and the wild saints of the forest and the desert. These were the people who built a real Christian culture. So did the simple, everyday lovers of God in the world, who tended to the poor and the sick for no reward. As the gates of Rome were breached by Goths, as Ireland and England were invaded by Vikings, as the Ottomans overcame Constantinople, as the communists dynamited cathedrals and crucified monks, they kept on. They did their work. They did not fight for civilization; they fought for Christ. And they fought not with swords, but with prayer and with active love for their neighbors and enemies. Without that love, the devil wins.

Christianity’s Imprint Remains in a Secularizing Europe (The Dispatch)

Katja Hoyer reminds readers that while secularization is firmly embedded in European culture, one cannot discount the lasting influence of Christianity in otherwise “godless” communities. She reflects:

In Europe, we may not go to church in the same numbers, but we still feel culturally embedded in the Christian tradition. Nowhere is this contrast more stark than in my home region. I have lived in the United Kingdom for several years now, but I was born in socialist East Germany, where four decades of atheist policies created what has sometimes been referred to as “the most godless place on earth.” The state collapsed with German reunification in 1990, but secularization continued. According to a study conducted by the University of Chicago, eastern Germany took a unique path in becoming and staying the only majority atheist society on earth.

…

Yet, even in East Germany, we were so steeped in cultural Christianity that the socialist dictatorship had to acknowledge its importance. The 500-year anniversary of Martin Luther’s birth, for instance, was marked with an entire “Luther Year” in 1983. Wartburg Castle, where he translated the New Testament into German, was restored at great expense in a state that permanently lacked building materials.

She continues:

Christianity acting as a cultural rather than a spiritual anchor to societies is a pattern we see around the world, including in the U.S., where secularization is commencing more slowly than in Europe. According to the Pew study, Americans unaffiliated with formal denominations still tend to be significantly more religious, praying to God in larger numbers. However, according to one long-term study, three-quarters of Americans now say they believe religion is losing its influence on American life, a number up from 55 percent before 2010.

Still, the decline in church attendance and the chipping away of religion from the public sphere don’t negate the role of Christianity as the bedrock of modern civilization in the West. Coming from a region where secularization was artificially accelerated, I believe what we’re witnessing isn’t the erosion of Christianity as such but its gradual transformation from a spiritual to a cultural backdrop. That makes me hopeful that ecclesiastical buildings—from grand cathedrals to rural parish churches—will never be “redundant.” We may not be sitting in them every Sunday anymore. But, in the words of Emmanuel Macron, they remind us that “we are bearing the legacy of something bigger than us.”

Study: Evangelical Churches Aren’t Particularly Political (Christianity Today)

Fiona Andre highlights a recent study on politicization among evangelical congregations — or, perhaps better stated, the lack of politicization. She writes:

According to the report, 23 percent of congregation leaders identified their congregation as politically active, but only 40 percent engaged in what the report calls “overtly political activities” over 12 months, mostly infrequently.

These activities, according to the report, include distributing voter guides, voter registration and mobilization, and “discussing politics,” among other things. She continues:

In nearly half of congregations — 45 percent — their leaders thought most participants didn’t share the same political views, making politics a sometimes treacherous topic. Discussing politics is also tricky for pastors, the report found, as they risk offending members whose views don’t align.

…

Instead of directly addressing political issues, the closest most congregations get to political discussion tends to be sermons that uphold specific values associated with particular political issues, such as immigration or abortion.

My Experience in the Negative World (Light Reading)

My friend Joe Dietzer reflects on his time as a student at John Brown University in the context of Aaron Renn’s “three worlds” framework. Joe is a thoughtful and attentive writer, and while he shares more than a few concerns about the direction of his alma mater, he also recounts a series of encounters with our university’s president following a chapel session:

I caught up to the president, and, getting his attention, asked him if there was a time we could meet. He said yes, and to send him an email to set up a time. A few days later, grateful for the opportunity, I had a half an hour time slot to meet again, in his office.

I was, perhaps, even more nervous before our second interaction. But I was prepared with another sheet of paper. He waved aside my honorifics and wanted to get right down to whatever questions I had. Soon, I relaxed. We had some back and forth about DEI, but the half an hour was quickly passed. It was friendly. He walked me out the door, and to my surprise, said, “If you want to ask me more of those questions you had on that paper, we can do this again.”

We ended up meeting many times after that—more than I can remember—where I was free to share my observations and opinions. As you can tell by the story, I am not an especially brave person, but because I was resilient enough to do something, I like to think that some of the things I said caught the president’s ear, and, I hope, influenced the school to draw away from its liberal drift. And it gave me hope for a brighter future because a college president was willing to take the time to listen to a student.

Why We Pulled Our Kids from Club Sports (The Gospel Coalition)

Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra shares a conversation with Dordt University’s Ross Douma about his experience with youth club sports, which Zylstra describes as “a nearly $20 billion market—even larger than the NFL.” Douma has mixed feelings about the landscape of club sports:

Sports and athletics are part of God’s creation. Like anything on this side of heaven, they can be used to really promote and glorify God, who made our bodies. They can also be a wonderful platform from which to share the gospel.

But sports can also become an idol. When our love for and pursuit of athletic achievement becomes greater than our love for God, his church, and the families he’s given us, we start to make wrong choices about how to spend our time, energy, and money.

Club sports can start off innocently, with a desire to use our bodies to glorify God. But over and over, I have seen it trap people in schedules they can’t get out of. I have seen their motivations change.

Integrating Faith with Athletic Identity (The Overtime Project)

Deverin Muff is a former NCAA Division 1 basketball player and current assistant professor of exercise science at Eastern Kentucky University. Deverin and I attended the same church for a time when our family lived in Kentucky, and since then he has become one of my favorite voices at the intersection of faith and sports. In this recent essay, Deverin reflects on the potential dangers of athletic identity:

A simple way to define athletic identity is the way athletes see themselves concerning their sport. Athletic identity comes with many challenges such as over-identification, retirement, and burnout. Many athletes who are entrenched in their identities struggle with an identity crisis when their careers end. That struggle often leads to a loss of sense of self which is called athletic identity foreclosure.

The purpose-filled athlete can provide a higher sense of worth beyond athletic identity…. In this view, the athlete sees sports as something that they do rather than something that encompasses their whole identity. For example, you become a person who plays basketball and not a basketball player when defining who you are and how you present yourself to others.

Faith plays a large role in identity because it acts as a guide for the athlete. It becomes a spiritual and moral compass to how one competes, how they deal with injuries and setbacks, and navigate the pressures of daily life.