"What the hell is wrong with these people?"

On the inevitability and pitfalls on evangelical "othering"

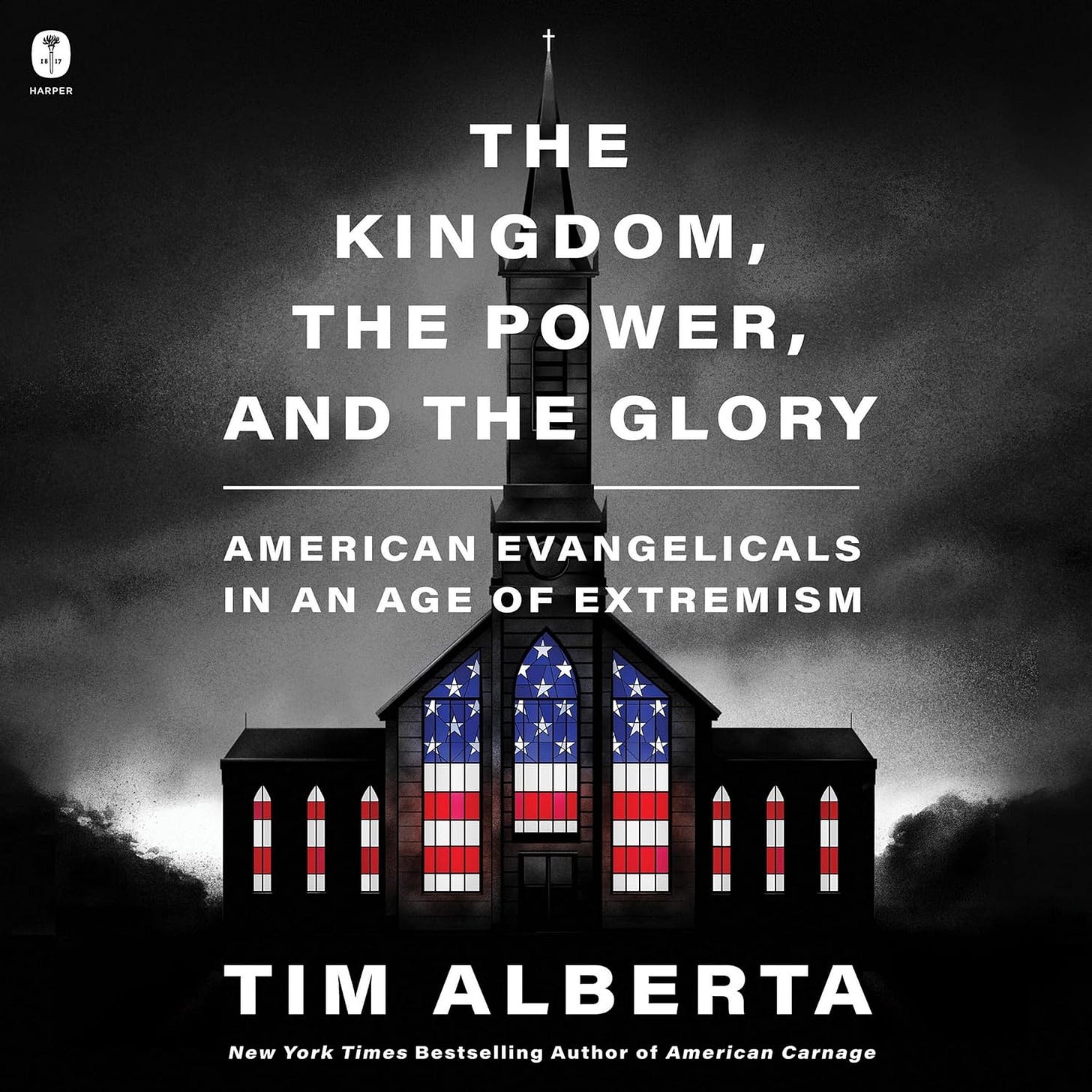

Over at Christianity Today I have a review of Tim Alberta’s latest book, The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory. The book is part memoir, part journalistic accounting of evangelical Christianity’s Trump-era transformation. As I wrote in my review, the book is “well resourced and eminently readable, providing a perceptive and sympathetic critique of American evangelicalism.”

You can read the whole review here. But I wanted to offer a few additional thoughts here:

Early in his book Alberta recounts a traumatic experience where, at his father’s memorial service, members of his church family chastised him for his political reporting critical of Donald Trump. In relaying this story to his flabbergasted wife, she asks a question that also serves as the book’s skeleton key: “What the hell is wrong with these people?”

It is inevitable that our biases and political priorities end up “othering” people with whom we disagree, including those sharing our faith convictions. I don’t believe Alberta set out to write a book bashing his evangelical brothers and sisters comfortably situated in MAGA politics. But that is how someone could read this book, given its criticism of this community and the author’s differences with Trump and the evangelical elites adopting Trump-style politics. In our era of extreme and toxic polarization, it is easy to conflate a sympathetic critique with a dismissive rebuke.

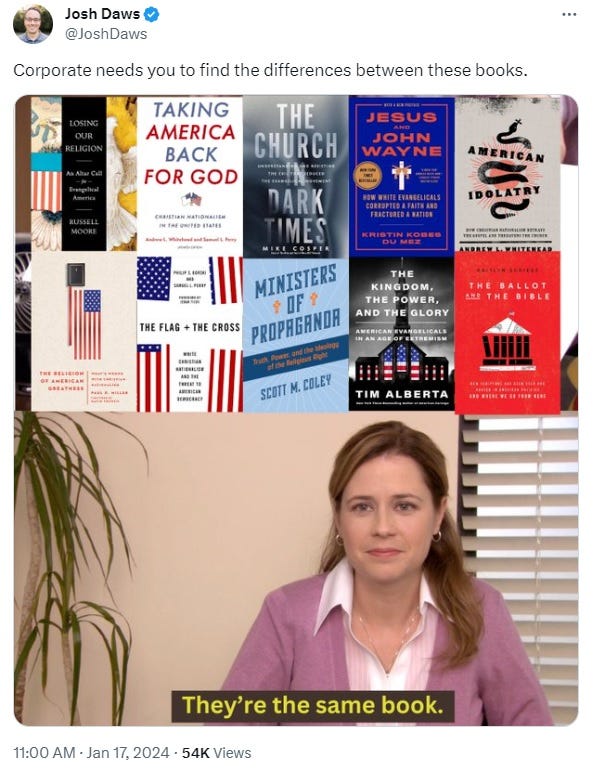

Over on The Website Formerly Known as Twitter, writer and podcaster Josh Daws provided a nice illustration of this phenomenon, using a meme originating from a well-known joke from The Office:

The way I read this joke (and Josh, if you’re reading this, you’re welcome to correct me if I’m wrong), because these books are written by authors with something critical to say of modern evangelicalism’s political tendencies, they are all worth rejecting in their entirety by evangelicals who are either sympathetic to Trump or outright supportive of his candidacy.

Are there similarities between Alberta’s book and books like, say, Jon Ward’s Testimony and Russell Moore’s Losing Our Religion? Sure — all three are essentially reflections on one’s evangelical upbringing and finding oneself disconnected from today’s evangelical environment. At the same time, it is disingenuous and dismissive to suggest that a memoir like Moore’s is substitutable for research like Kaitlyn Schiess’, or that Paul Miller’s book on Christian nationalism is somehow identical to Jesus and John Wayne, just because each has something critical to say about elements of conservative evangelicalism. It’s an intellectually lazy and critically unproductive argument.

For Christians, it can be tempting to “other” Christians with whom we disagree on political and cultural issues, regardless of where we find ourselves on the political spectrum. People like Daws will “other” people like Alberta as insufficiently committed to a Christian faith this age demands, while people like Alberta will “other” people like Daws for losing sight of what his faith should really be about. As I wrote in my review of Alberta’s book, it is only natural to make ourselves the heroes of our stories.

And this is where we must be self-aware. We have to be willing to read, hear, and learn from people with whom we’re predisposed to disagree, especially our brothers and sisters in the church. This doesn’t mean refusing to debate, correct, or voice opposition when we disagree. We don’t have to buy what others are selling. But if we don’t engage at all, and in good faith, we’re not treating our brothers and sisters as made in God’s image. We can identify errors in others, but only when we actually engage with them.

It’s comfortable for us to instinctively dismiss people not fitting into our own silos or echo chambers. But for Christians called to abandon the habits and tendencies of the world, we should strive for something richer and more inclusive.

Alberta spends some time later in the book focusing on evangelicals’ traditional alignment with the pro-life movement, Donald Trump’s three Supreme Court appointments marketed to evangelicals as poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, and the 2022 case—Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health—that did just that. Alberta argues that while Trump’s presidency delivered the pro-life movement’s biggest legal win ever, the consequences for the politics of abortion are anything but settled.

For example:

Once a controlled and regulated medical issue, abortion became a wild-west patchwork of policies in the aftermath of Dobbs. Some red states rushed to ban the procedures entirely. But many more blue and purple states, now liberated from any overarching federal framework, pursued laws that made Roe v. Wade look conservative by comparison. (307)

He goes on to describe how abortion rights fared well at the ballot box in several states following Dobbs—including in red states like Ohio and Kansas—and how this is evidence that the pro-life movement may be like the dog that caught the car. Still, I don’t think many pro-life activists would trade the demise of Roe for a more stable political landscape involving abortion rights; for these activists, Dobbs was a necessary first step.

Furthermore, while it’s reasonable for Alberta to highlight supposed inconsistencies in the pro-life movement’s agenda—opposing abortion while, say, opposing social services for women and children—I’m not convinced that the pro-life movement’s general alignment with Donald Trump is going to be as damning for this movement’s long-term goals as Alberta seems to believe. Abortion was politically divisive long before Trump’s 2015 descent from his gold escalator.

Finally, it was amusing to see myself in at least three of this book’s accounts. First, Alberta wrote about a memorable lecture Russell Moore gave to college students and professors at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute. I was at this event, and found myself sitting next to Moore as he prepared to give his talk.

Second, Alberta highlighted the work of the American Values Coalition in pushing back against the spread of misinformation and polarization among evangelicals. I’m on AVC’s board, and later this month will be traveling to Phoenix for what is looking to be a promising conference for pastors and church leaders.

And third, in a section on the transformation of social commentator and radio host Eric Metaxas, Alberta wrote:

In a livestreamed debate with David French … Metaxas left their Christian college hosts slack-jawed when he responded to French’s opening argument by quipping an old Saturday Night Live joke: “Jane, you ignorant slut!”

John Brown University hosted this debate, and I was one of those slack-jawed hosts. With more than 100,000 views on YouTube, this 2020 event has to be among the most-watched thing JBU has ever done. Which is… something, I guess.

I’m always hesitant to write reviews of books like this, especially for popular outlets with sorted readerships. It is inevitable that people are going to see that I, a political science professor at a Christian university, wrote a review of a book that’s getting a lot of positive attention in the mainstream media for a website that has alienated (fairly or not) many on the political right during the Trump era, and let their heuristics do the rest. I guess that can’t be helped.

Still, The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory is worth a close and careful read, even if you find yourself taking issue with some of Alberta’s characterizations or conclusions, as I at times did. There is a good deal to learn in this book, whether you’re trying to understand the worldview of Trump-adjacent evangelicals or this movement’s critics.

Daniel, this would make for excellent content on the show, Monday. Can we plan to discuss Tim Alberta's book but also the observations about Christian othering?

I've long since left Twitter but remember Daws very well, sadly lazily grouping together a bunch of books he hasn't read to throw red meat to his followers sounds entirely in character for him. I listen to Schiess regularly on her podcast and she doesn't harp on Trump or how awful evangelicals are at all, rather that we should engage locally as opposed to consuming media. I guess the one thing all these books have in common is that they in some way advocate changing the evangelical approach to politics that has been tried the last 50 years and is self evidently falling apart.

You do have a good point about othering. I do think Alberta would be more than happy to take that criticism based on the book and interviews he's given about it. The book does end on a hopeful note that did help, halfway through the book it was one of the most depressing books I've ever read!